Memories of a border hopper

On the face of it, to envy-prone people a resumé of Mark Reeder’s life might cause them a problem. Almost everything adds up. For example, the first album he bought was “Electric Ladyland” by Jimi Hendrix, he experienced his pop-education in Manchester’s first Virgin record shop, he knew Ian Curtis and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson and played in his first band with Mick Hucknall – yes, that Hucknall, later founder of Simply Red. Should, I say yes, it’s all true, well, I guess “almost” everything is true.

It was in the initial glow of punk, that Reeder gave up his career as a commercial artist and broke free, eventually bringing him to Germany. There he became Factory Records man-in-Berlin and a connecting point for many British bands on tour. Later, he became the manager of all-girl group Malaria! and live sound engineer for bands like Die Toten Hosen. He appeared in Jörg Buttgereit’s controversial horror movies “Der Todes King” and “Nekromantik 2” and reported from the walled-in city for BBC and the UK’s mould-breaking pop music show “The Tube”. After the fall of the Wall, Reeder formed his own label MFS which became known for its trance-y techno and for launching the careers of Cosmic Baby, Johnny Klimek and Paul Van Dyk.

Reeder was also the port-in-a-storm for a certain confused Australian called Nick Cave whom he picked up somewhere in Europe and helped persuade him to move to Berlin, granting him exile in his small crummy Kreuzberg apartment. This was probably quite easy, because in most cases the two suit-clad artists were never at home in their cold coal oven room, but to be found hanging out in the warmer Berlin clubs and bars. Cave eventually moved back to England, however Reeder stayed and he still floats around Berlin today with his unique aura, still interested in and absorbing everything, just as he did over thirty years ago.

Mark Reeder’s starring role in the documentary film “B-Movie: Lust & Sound in West-Berlin 1979-1989” came purely by chance. Initially he was engaged to work on the soundtrack because the director had heard his CD album “Five Point One” and had the idea of him reworking the films songs in 5.1 surround. But when the producer Jörg A. Hoppe, Klaus Maeck and Heiko Lange realised that they had before them one of the most well-documented protagonists of Berlin’s music history, he became the film’s subject and locus, opening up a view deep into West Berlin’s 80s sub-culture, as seen through the eyes of a Brit.

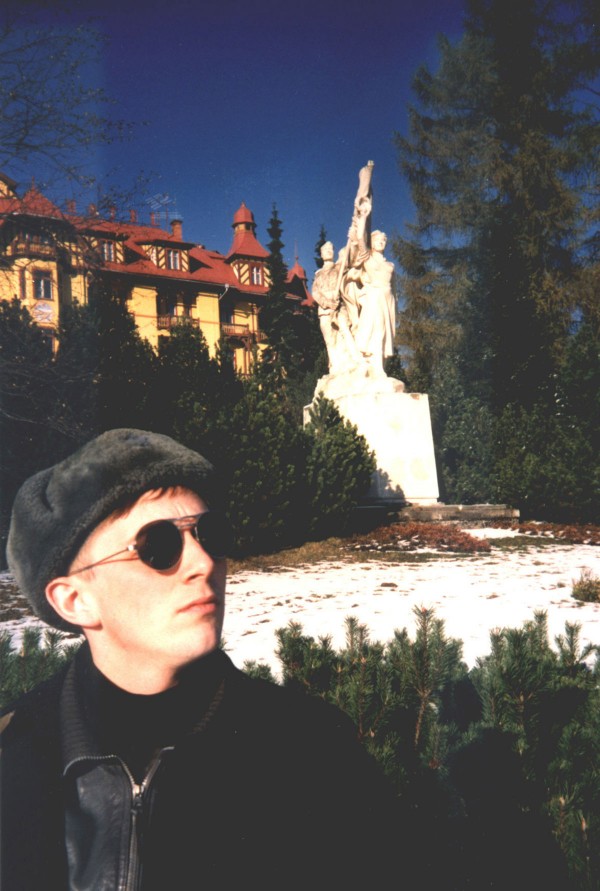

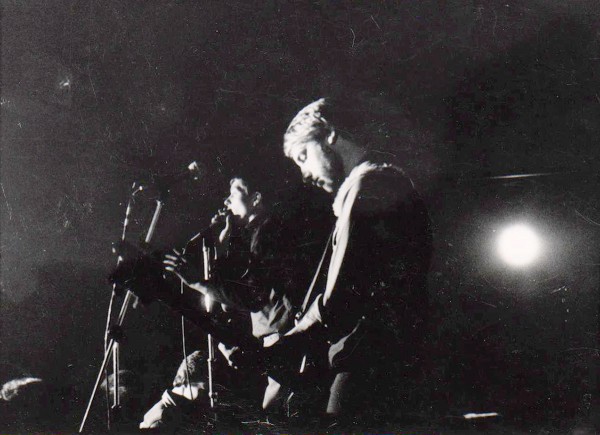

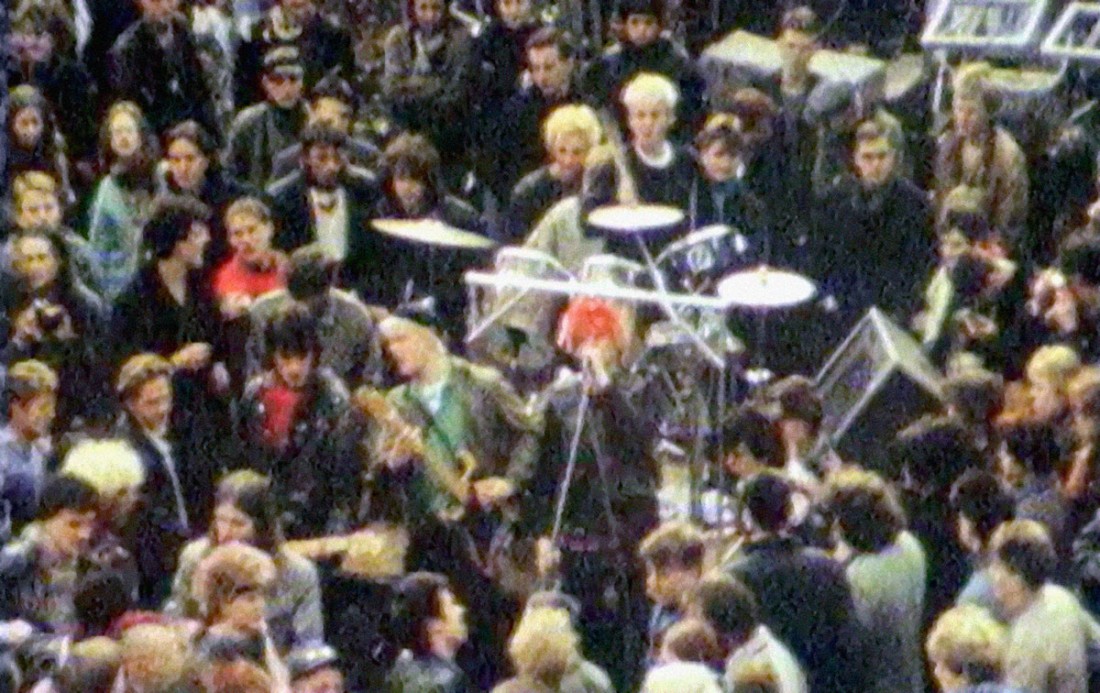

For Kaput, Mark Reeder has kindly dug out some private photographs from the 80s and 90s, and talks about the changes that he has seen in the city since those days.

Mark, although this interview is not only about your film, but about your wider knowledge of the history of Berlin, let’s still obviously start with this. How did you become so centrally involved in “B-Movie: Lust & Sound in West-Berlin 1979-1989”? Was it that there is so much video and photo material of, for and with you?

That’s right, in retrospect it’s weird how much material there is with me. Originally, the film was planned differently, Jörg A. Hoppe, the former manager of Extrabreit and Heiko Lange intended to compile a fairly normal documentary about West Berlin in the early 80s. Jörg knows a lot of people and was confident he would be able to get enough material. At the point when I came on board, they didn’t really have a detailed narrative. Jörg had heard my “Five Point One” album, for which I had remixed songs by Depeche Mode, Pet Shop Boys or Anne Clark in 5.1 cinema surround, and he found it interesting and wanted to know if I could produce the soundtrack for the film in 5.1 surround. We started talking and I mentioned in passing that I also had some footage from the period, from documentary programs that I’d produced about Berlin. It quickly became clear to him that the film should be made from the perspective of an Englishman: a outlander who is also an Inlander. They wanted to present my view of the Berlin scene and the question of how I became a part of it. As I was not just an outsider who had experienced something for a few days but I had played an active role in it. Suddenly there was a story.

The way the film has been put together certainly isn’t without its problems. One sees and hears you in the old material, but all the other voices, from people like Gudrun Gut and Blixa Bargeld, speak from the present. One can only hear them and not see them. I’d like to have seen Gudrun and Blixa.

It was intentional, not to be like that. We didn’t want to make a typical documentary that just shows a load of well-lit talking heads, set before a dark background while showing some old footage and speaking in the present about how great it all was back then. We purposely didn’t make it like that because we simply wanted to just tell it how it was. That’s the main difference.

These pictures speak for themselves and people talk from the past and not about the here and now. It’s not a glossy story.

Apart from your own archive, was it easy to acquire all the images?

If you decided to avoid the images from the present and use only original footage, you must have had a mammoth task before you?

It was a massive accomplishment that swallowed up three years. But even more than the external search, the producers then added to it my own archive. I kept finding new footage at home. So much so, that even as the film was in its final cut stages I still kept unearthing new video tapes. Eventually, in the end they were screaming at me and pleading with me not to find any more footage.

In reality though, our film owes its thanks to over 70 directors, all who at one time or another have pointed their Super8 cameras for two minutes at something interesting and so documented images that would otherwise not exist.

This immediately raises fascinating questions about memory. Especially in comparison with today where everything is constantly being recorded, documented. I’m sure that if you would at some point, compare the material from the 80s with which you worked, their motif is much more interesting, because today’s new visual opportunities bring a sort of blurring effect with it. Whoever fired up a Super8 camera back then, knew exactly why they did it – today’s smartphone shooter seems only aware in the rarest of cases.

Absolutely, with Super8 you only had two minutes of film roll – and they were also very expensive to buy and develop. So you had to choose your shots carefully. Of course there were snapshots that were not planned, such as the terrible scene we show, where Klaus-Jurgen Rattay was run over by a bus. But then, with staged scenes like the Mauergeburtstag (birthday of the Berlin Wall) Knut Hoffmeister knew that he would set fire to the wall and that he would film it. The luxury of spontaneity we have with today’s technology, was rare back then.

What makes your images so special, is the fact that most of the footage was either forgotten, or previously unseen. Indeed, no one knew of its existence and now you are confronted with it. By contrast, current images are uploaded almost in real time onto Youtube. Therefore it never gives rise to a real feeling of scarcity, as the archive is seemingly permanently open.

There were maybe five or six people who you would regularly see with a camera. That’s why we had to do a lot of research for the film to find out who had filmed what, when and where. Manfred O. Jelinski the old partner of Jörg Buttgereit, had tons of material in his archive, as he filmed a lot of concerts in SO36 – luckily on a better 16mm camera. He told me he has thousands of hours, most which has only ever been seen by him.

Amazing, that with his experience of film distribution, never came up with the idea to do something like this himself with his own material?

He did, he made “Das war das SO36” video from which we took some snippets. One forgets at some point that you have, what turns out to be culturally important footage. It was a similar situation for me, for example take the footage from “The Tube”, I had never actually watched it. I received the tapes and just put them away in a box and forgot about them. It was only when Joerg Hoppe told me of his idea, that I remembered I still had this stuff somewhere.

Which probably has something to do with the fact that your lifestyle hasn’t really changed much. Okay, you might need more sleep than in the 80s, but ultimately you are still culturally active and interested as always, that leads you not to constantly dwell on the past, unless of course you are prompted through a creative process, such as with this film. Was it strange for you having to recall the past?

Oh yes, it was really difficult. Life in Berlin is an ongoing process for me, in fact, so I’ve never viewed the things I do or did in such a way that I would have to remember them years later for a documentary. We didn’t actually plan anything, if someone came up with a good idea we just fell from one thing into another. To have to remember everything in detail after so many decades have passed, is a very difficult, almost impossible process. For example, there was some black & white video footage from the Risiko that Heiko Lange showed me. He wanted to know if I could remember the event, was I there or not. I couldn’t remember it and so was absolutely certain I wasn’t there that night, then he slowed down the footage and there I was in the corner, sitting at the bar, while Neubauten were preparing a performance.

Is this disappearance the result of your former wasted lifestyle or the unremitting interest things that are new?

A bit of both. You get older, you forget the little insignificant things that were not really impressive, you remember only those moments that have engraved themselves into your consciousness. Recalling an evening at Risiko, when we were all in some way fucked up? Back then, it was like that every night.

Ahh, wild old Berlin. But is that not just a legend? Do you feel, as someone who is enshrined in the current Berlin, that the difference is really that big?

It is another Berlin now. The drugs and debauchery are quite the same.

I do not miss the Berlin of the 80s. Today is much more relaxed, you can move around more freely. But I sometimes miss the wall. In that sense I mean the thrill of crossing the border. It was very exciting to go into the East and to help the people by smuggling stuff over for them.

You mean you can no longer live out your Samaritan role?

Yes, I miss being able to help the people over there and do something good for them, by supporting their little music scene. The excitement I find in the current Berlin is another. I don’t find the club scene as thrilling as before that’s why I don’t go out every night anymore.

But that’s more likely because of you and your age than with the scene.

Yes, of course.

That leads to the question is the difference for a 20 year old today so blatantly different?

From what I’ve discovered, the 20 year old of today always wants to know how and why we made our stuff back then. What kind of a world spawned a band like Einstürzende Neubauten, who produced their music with discarded building materials? From today’s perspective, it is practically inconceivable that a band like this could be successful. That was the excitement of the Berlin scene back then – it was a totally unconventional era. This was due to the specific situation of Berlin. The city was a refuge. There was no pop culture stress. Especially for me, who came from a vibrant British pop culture where everyone wanted to make music in order to escape the misery of unemployment and lack of future prospects. In my hometown of Manchester most bands in the 70s hoped to land a hit and escape to London or America. In Berlin it was different, the people here had already escaped.

Once in Berlin a West German was exempt of his obligatory military service in the Bundeswehr. The city became a melting pot for gays, trannies, draft dodgers, old women and all those weirdos who did not fit into their small little village society. They all came here and met like-minded people.

Berlin felt so exciting and fresh, much different from everything I knew from England.

I was (and still am) constantly inspired here, due to the creativity which surrounded me from artists, musicians, illustrators, to film makers and the like, all of us united through music. You played an active part in what went on all around you and we never gave a thought as to how others would reflect upon how we lived.

But the difference to today is that the drab, rough and tough still had an appeal. Today the subcultures are still as present and there are more places than ever where you can get drunk and dance the night away, the drugs appear even more exaggerated than before, but it all looks a bit more like a stylish health club. It has been given a different aesthetic.

It has become a modern world. Unfortunately. The order of things, which we had earlier, has evaporated. Take a legendary club like the UFO, if you asked a 20 year old today, how he imagines this club was like, it is nothing like they can imagine, when I tell them they are usually flabbergasted.

There was no monster doorman who aggressively searched you. There was a pleasant Asian girl standing with her brother at the door and they would let in anyone they thought would fit in. You weren’t intimidated by pressure or insecurity. It was very relaxed.

Less of a controlled society.

Not really, there were almost no controls, if you looked the part you were simply just let in.

You could also get by with very little money, you talk about it in the film – but what did that mean for the quality of life? And is it in your opinion still possible today? When compared to the other major capital cities of the world, Berlin is indeed still very cheap. We end up again with the same question: Is it not rather a question of age as of the era?

Back then, most of our flats were very cheap. There was no central heating, you had a coal oven heater and you always had to slog it to the coal merchant if you needed fresh coal, that was much harder in winter. In addition, most cheap flats had outside toilets, which meant you had to go down two flights of stairs just to take a quick piss. In some flats you didn’t even have hot water.

The fact that many of us lived under such circumstances, ensured that we went out to clubs or the bars for the entire night just because it was warmer. Sure, you met your friends or new people, danced and took drugs, but the fact that your flat was uncomfortable, cold and dreary also played a big role and Risiko and the Dschungel were much warmer and friendly places.

How did people finance a permanently going out lifestyle? Yes, you knew a lot of people and you were often invited for a drink, but somebody had to pay for the tons of drugs and alcohol?

We didn’t really think about it. When you had money you invited people and were invited in return. One was constantly invited.

Did you not have a job at that time?

When I first came to Berlin, I jobbed about here and there just to make ends meet. Then I became a live sound engineer and later the manager of Malaria ! but they didn’t have a concert every day. Live sound mixer became my main source of income, I did that for the Toten Hosen or bands like Family 5 and for bands from England, just to make a bit of money. But there were occasions when I had nothing and had to think what can I do to bridge the gaps. For example, I once developed microfilm for Bayer. This was a six-week holiday replacement cover job. The fact that I was a trained commercial artist, I could earn enough money so that I could live off it for six months. That kind of quick job thing really no longer exists in that form today. Even my former television jobs were also very well paid that I was able to live practically a whole year from each of them.

On the subject of money. In retrospect, when do you think it became legitimate within the scene to perform in a business manner?

That actually happened only after the fall of the wall. Until then, even something like running a club was operated in an alternative way. Even Dimitri Hegemann started Tresor under such naive business circumstances. But after the reunification, as more business-oriented people from West Germany came into Berlin, people started to think differently about their business. Much was due to the fact that the Berlin subventions and other benefits were cut. Instead, people came from other places with money, such as England, Spain and Sweden to invest in the city.

There became a commercialization of everyday life?

Yes. These newcomers brought serious forms of business with them, much more professional. Up until then, everything had been rather unprofessional here.

You frowned upon the idea of being designated as Malaria’s “manager”..?

I never wanted to be known as their manager! I never introduced myself with the word, to me it had such a bitter aftertaste. I said at the time to Gudrun Gut, that she should never introduce me as their manager as it sounded so terrible to me. We all wanted to be successful, but on our own terms and not in the same pop historical way like Nena or Markus, but popular in a truer form, one that had been achieved through reaching a greater amount of like-minded people.

You mean, to quote the French philosopher Pierre Bourdieu, you sought to gain more social acceptance and cultural capital?

Yes.

Can you remember when you first registered the moment when such an improbable success story for the previously mentioned Einstürzende Neubauten looked possible?

When they appeared in Bravo magazine…. Many of the people at that time who did nothing other than make music, were often asked by ordinary working people what their regular job was. The concept that you lived from music, tried to get a band gigs or accompanied them on tour and mixed their concerts was an insecure and unfathomable way of making a living. We never thought about what the future would look like. However, we noticed at some point that conditions had begun to change. Suddenly there was a huge positive response to the concerts, we had requests from abroad, all through word-of-mouth advertising. From one day to another new opportunities began to arise.

Was there criticism? Because when popular local bands start to play outside of their own city, this indeed can lead to vaccancies back home – and through their abcence the local scene can change. You can see that today, that it has become much more difficult to create a new Seattle, since conditionally, the opportunities that a global platform presents today enables an artist to reach a much wider audience but it also can limit their period of popular existence.

Honestly: We were always glad to get out and have a chance to stay in a nice hotel. You did not have to bring the coal from the basement. We were proud for the others who achieved that. But I must say, I was always glad to get back home, no matter how difficult it was and under what dreadful circumstances we lived. These tours were a bit like school trips where you presented yourself and your music.

The image that you created through the international gigs, gave a picture of success abroad, which also attracted sometimes strange gig requests. I remember there was this promoter of Sektor, a sadly stillborn Club on the Hasenheide. He wanted the Malaria! girls to perform at his club because he wanted it to look cool and credible and so he offered them DM10,000 marks to play, because he obviously thought, as they play internationally in USA or Holland, they must be really expensive.

Have many of the people who surround you at that time, fallen by the wayside? In an artistic sense, that they lead today very different lives than just a purely physical one through the change in living conditions?

You fight for what you believe in. But if you decide on drugs and alcohol, then your route is predestined. I was never like that. I live for music.

But I have never perceived it like old friends dropping off to be replaced by younger ones. Although there’s maybe some indirect truth in it, the truth is I have just kept going. You meet younger newcomers along the way. The younger people, with whom I now hang out with, I see as like-minded people, we are interested in the same kind of music, art or movies, we go to the same type of concerts. Their life today has little in common with ours in the 80s and 90s. Today, everything is much more convenient than before. Even if they sometimes perceive it as being difficult, I’m sure they can see the difference. A good example is diet. I was already a vegetarian back in the 80s and to go on tour as such was always very difficult. In a Bavarian backwater once they only had made suckling pig for the band. So I had to make do with a Gulag menu of bread and water.

The former scene stuck to something very snobbish: either you belonged or did not belong. So someone like Blixa who funnily enough at the beginning of the film appears almost like an innocent boy, but then quickly, he developes his own particular style that characterizes him still today, he embodies this attitude very well.

That was simply the mixture of image and drugs. The interview scene, which you mention in the film where he looks really fucked up, was arranged at a time when Blixa had just woken up and he was in a really difficult mood. He didn’t really want to do it, thought it was stupid, he didn’t want to get on with the interviewer, but then again he did it.

I ask this because I would still like to talk to you about the “fly-on-the-wall TV” narrative style of documentation. The portrayal is not quite quite the harsh environment of speed snorting types, lying comatose in front of their coal ovens, which we have heard about from that time.

Interesting point, I have never thought of the film being seen from that point of view. When I helped to plan the TV programmes for British telly back in the 80s I decided I wanted to present my exile to my countrymen in a certain way. I wanted to show them that a different mood existed in Berlin compared to the UK.

I do not mean from the archive material, but your recorded narration from today, that guides the viewer through the documentary.

I did not want it to sound so complicated. People from all over should be able to understand me. Our original script was much more detailed about what went on, but ultimately we only have 90 minutes to tell our story – a decade in 90 minutes is not easy to achieve. Producers Joerg Hoppe & Klaus Maeck put my story together and gave me their ideas about how they would like to tell it, and I then wrote my English narrative part on this basis, I sent it to them, they wrote back with amendments and we ping-ponged the story until we had a final version. If we had left it as it originally was, the film would probably have been a three hour epic, like “Apocalyse Now” – so we sadly had to cut stuff out and make harsh compromises. It is very difficult to explain this period in just a few words. I’m not Goethe, but I wanted it to be a simple narration, so as to create a film for a wide range of people and for it to be understood everywhere, so that people can see how we lived back then. Whether they come from Mexico, Singapore or Turkey, all of them should be able to understand how Berlin looked like back then and what we got up to. If you make it too complicated, then some people might not fully understand it.

Mark, to which part of Berlin would you send a young person, if you wanted them to get the best impression of the city, one which comes as close as possible to the old Berlin?

I would send them to the outskirts of Berlin, it still conveys the two sides of the city in the 80s and gives a rough idea of the duality of East and West Berlin. Simply take a tram to the end, direction Landsberger Allee and beyond!

In our film, we actually only show a brief snippet of East Berlin because our film is about the island of West Berlin – these days people know even less about the West part of the city, the East has been given so much more coverage. The Berlin special TV programme, that I put together for Britain’s popular TV show “The “Tube”, was in fact the very first time that a pop-cultural music program had ever been produced in both East and West Berlin. I must say that without East Berlin I probably wouldn’t have stayed in Berlin that long. I found it fascinating. I didn’t only make a lot of trips into the German Democratic Republic and the whole Soviet bloc, but I also built up a circle of friends over there too. Berlin was always one city for me.

Did you intensify your friendships after the fall of the Berlin Wall?

With the fall of the wall I automatically got to know new people from the East. On the other hand, the fall of the wall had an immediate impact on my original circle of GDR Friends: some suddenly disappeared entirely from my life. This naturally raised the question of whether they may have worked for the Stasi? Ultimately, there remained only a very small circle of close friends, but I also got to know many new people too, especially through the flourishing techno and club scene. When I founded my label MFS (Masterminded For Success), in East Berlin, my first idea was to create a platform that would initially serve young East German artists.

I thought, there are probably lots of young East German artists who are simply bursting with creativity and many, who don’t even know they are creative yet.

My label was supposed to give them an objective. The problem was that the Eastie kids didn’t own any technology to make music on and it took a while before they had the cash to buy instruments and learn their way around a computer. It didn’t deter me though and I carried on searching until I eventually got to know a few. They all had dreams and ideas and I thought it my duty to help them to realise their potential. To accelerate the process, I coupled the Eastie artists with my Wessie artists.

Speaking about your dance label MFS, we’re still right in the middle of the Techno boom of the 90s. We have already discussed the differences between the ’80s and today, so now lets speak in detail a bit about electronic music: what is the difference between the current techno scene in Berlin from that of the 90s?

Quite a bit really. Back then, everything was new, untouched and fresh. Totally new ground. Not only the venues along the former border were new, but the was music too. Techno music evolved really rapidly as more and more people discovered they could also make this kind of music. This had mainly something to do with the rapid development and price of the available technology, ATARI computers and the music programs such as Cubase were suddenly affordable. The creativity was driven by energy and euphoria and you could more or less do anything you wanted. Everything was allowed, because there were no limits! Ecstasy also played a big role too. It was a relatively new drug, and it was to be found at every party, and it put everyone in the same state of mind.

The music united us all and we all loved each another. That was especially important. E opened every closed door to techno. Before the fall of the wall, the only drugs available to most Eastie kids was nicotine and alcohol. For sure, many had heard of drugs like speed, marijuana or lsd and maybe one or two people had actually tried it, but for the majority of citizens in the GDR it was unavailable and mythical. Then suddenly, the wall was gone and with their new found freedom, drugs were instantly available, for a small price you could get really shit-faced and dance the entire night away on E. In addition, techno music became the music of choice because it was the ideal soundtrack, instrumental, hard, fast, repetitive, hypnotic, metallic but not melodic.

Some of my older friends couldn’t get their heads around pure techno initially. I was thinking how can I mix the hypnotic techno element with some kind of seductive hook line melody in the hope I could entice them. I wanted the music to reflect the inner feeling of euphoria, optimism and happiness that came with a newly reunited germany and thought that must be possible somehow. Emotional sounds and melodies fused with techno. My intention was to play with people’s emotions, that the music should mirror the feelings that people usually have while on E. I originally called the MFS sound hypno-trance, then it became trance-dance, really just to separate it a bit from the harder form of techno and eventually it became known as just trance. If you listen today to the first MFS compilation Tranceformed from Beyond, then you will notice it sounds virtually nothing like the current interpretation of the genre. Back then, even techno was warm and futuristic. It was inventive because it was all new. It still is inventive today, but in a different way. Yet the guidelines have long since been set. What really impresses me about techno is its shelf-life. Since the 60s trends had always been relatively short 3 – 5 years maximum, then they would change into something else, techno has survived over 25 years and has continuously developed and stayed innovative. It’s all due to technological development. The emergence of new or retro synths and computer programmes, helps to maintain the consistant reinvention of techno and keep it alive.

Mark, you are mentioned in the book recently published by Andreas Dorau and Sven Regener “The Trouble With Immortality”. Andreas says he produced some trance tracks with Tommi Eckart, under the project name Volumina, which he released on your label MFS. The track was called “It’s Alright”. We leave the 80s for the moment to reflect on this as I’m interested to know, do you remember the encounter with his music at the time?

Yes I certainly do. I received a demo cassette tape with a track called “transformation” by his project called Transform. A super track, which I thought would fit perfectly on my label and I wanted to release it on MFS. Unfortunately, there was a tape mix-up and instead I got Volumina! Apparently, they had sent me the wrong cassette and “transformation” was already licensed. Since I already knew Andreas, I called him and offered me a track by his other project with Tommi Eckart, Volumina. OK, it wasn’t the hammer track like Transformation, but similar in Tommi Eckart sound and style. I still went ahead and released it. As an A&R you had to look beyond a single and think about the broader picture. I was looking towards building artists to make albums. I thought, motivation is a huge factor in driving artists to push themselves and a single release is such a motivator. Who knows, maybe their next single will be a better composition. Sadly they only ever made that one Volumina single.

A slightly absurd final question: If you had to choose a special night to be the best one that you’ve ever experienced in Berlin, what would it be?

Of course there are quite a lot, but one of the most interesting and versatile days was the second secret gig of Die Toten Hosen in East Berlin back in 1988. The day before, the band played a benefit concert for Trevor Wilson’s Ich und Mein Staubsauger magazine and we used the opportunity to take the band over to play another secret concert in the East part of the city. Again, it was part of a so-called “Blues-Mass” in the Hoffnungskirche Church in Pankow (roughly speaking, prayers with singing) together with the East Berlin indie band Die Vision and disguised as a benefit concert for starving Romanian orphans. Using a US soldier friend of mine, we smuggled in to East Berlin a load of East German money, a huge bag of hash-biscuits and the bands guitars and bass – something which was not possible at the first secret Eastie concert of Die Hosen five years earlier, in 1983. My Eastie friends tried to keep the concert relatively secret, but there came over a hundred people. When we arrived from the border, there was already a Volks-police car waiting outside the church grounds. So we knew then that the gig was no longer a secret.

We decided to go ahead with the gig anyway. Of course due to the police presence, the atmosphere had become very tense and we were all shaking with excitement (and cold), because we really did not know what would happen next. We expected to be spending the night in jail. Die Vision performed first and played a few of their songs, and then just as the Hosen were about begin, the priest read out the sad news that because an ice age had begun to cover the country, the authorities had forbid the appearance of the Hosen and they couldn’t play. We quickly told the priest that he should announce that a band from Dresden would play instead – We suspected that neither the Stasi nor the East German police would know what the Hosen looked like, and in fact, they played for almost an hour before our deception was discovered.

After the concert, we went for a slap-up meal with a huge punk troupe in tow, to the flash House Budapest restaurant on the Karl-Marx-Allee, which we had reserved days earlier. They obviously thought we would be coming with 20 US soldiers and were of course totally shocked when this bunch of dishevelled looking punks and decadent, drunken and very biscuitized foreigners appeared as their guests. Because of the hash biscuits, we were all very hungry and so we ordered everything that was on the Menu and drank the most expensive Hungarian wines, all paid for with the smuggled Eastern money. Since we had to be back at the border crossing by midnight, our US soldier friend broke all of East Germany’s traffic regulations on the way back to the border crossing and driving through every red light and even the wrong way down a one-way street – he knew that only the Soviet military police could arrest him, but not the Eastie Volks police. After our mad dash, we arrived just in time at the Tränenpalast (Palace of tears) East/West border crossing. Campino, who stood a few people before me, had initially concealed his strawberry red hair under a cap whilst entering the East that morning, because we knew they wouldn’t have let him in to the GDR otherwise, but now it lay uncovered for all to see. The flabbergasted border guard looked at this outrageous looking figure before him and asked him which idiot had let him in. Whereupon Campino cheekily replied “One of your idiots!”. He was then hauled off for an ass check.

Once back in West Berlin, one of my friends from the day, Dave Rimmer and I delved deeper into West Berlin’s nightlife and wenton to a party in a disused S-bahn train station, we later ended up in the Metropol, which in those days was the biggest gay club in Europe. We danced the night away until morning. Before parting, we laughed about the day and how we had experienced such a diverse pallette of Berlin’s music culture. That was truly an unforgettable day!