“One of the last true punks” – Alan Bishop and the Invisible Hands

Kaput talked to Marina Gioti about “The Invisible Hands”, the documentary she directed and produced together with Georges Salameh about Alan Bishop (Sun City Girls, Sublime Frequencies, Alvarius B) and his band The Invisible Hands.

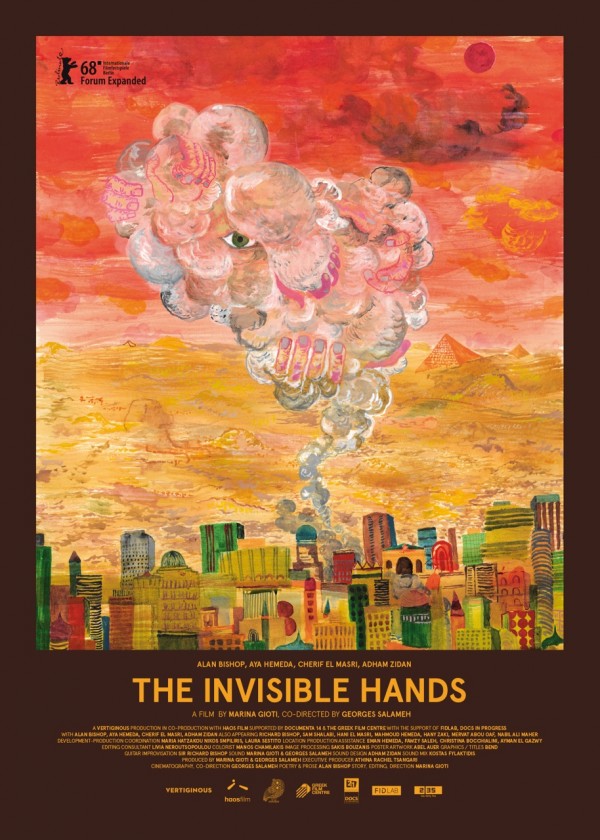

“The Invisible Hands” will premiere during the Berlinale (in the Forum Expanded Sektion) at Akademie der Künste (18.2.) and will have a repeat screening at Arsenal 1 (19.2.). The Cairo based band The Invisible Hands will perform live on 20.2. at Silent Green.

Marina, could you give our readers some background informations on you: your upcoming, artistic socialization, past and current work….

I am a filmmaker and visual artist born and based in Athens. My first degree was in Chemical Engineering, which I studied but never practiced after moving to London and studying film a few years later. I make films and media art installations. My latest piece and current research is in sleep science. I ‘invented’ an environment/ installation that uses medical data of sleeping people and ‘translates’ them into kinetic sculpture, light and sound. I am also a dj, or more of a music selector, for the past 18 years, which is something that has influenced the way the way I edit, which always central to the films I make.

The cinematographer and co-director of the film, Georges Salameh’s is a Greek-Lebanese filmmaker who has a parallel career as a photographer. He is one of my favorite photographers, actually. I love the way he observes people and landscape. He comes from a family of artists from Lebanon that moved to Greece during the war in the 80s. He speaks five languages and fits in any place you put him. He is also based in Athens.

How did you come up with the idea for “The Invisible Hands“ in the first place? What´s the genesis story of the project?

I met Alan through music, in Athens actually in 2011. With my friends, we used to organize small experimental/ improv shows locally. For one of these shows, we invited “The Brothers Unconnected”, Alan and his brother Rick, the successor band to the Sun City Girls, after their dissolution. A year later I met him at a festival in Belgium where I was living at the time. He told me that he had moved to Cairo and was working with young Egyptian musicians who were translating some of his old lyrics into Arabic. I was intrigued and spontaneously asked if I could come to Cairo and document the project.

He was immediately positive, to my surprise. I was obviously a fan of Sun City Girls and Sublime Frequencies and his solo projects as Alvarius B, but as an artist I was more interested in Alan’s unique artistic process, in the influence of other cultures in his work and particularly his DIY modus operandi, as I consider him one of the last true punks. The idea kept swiveling in my mind for a few weeks. I talked to Georges about it and he was also convinced straightaway. So we booked our flights to Cairo at the time when the band was recording their first album, that coincided with the first democratic elections in the country after the 2011 uprisings. It was simple as that, but later of course it proved a giant leap of faith and, as in most documentaries, a journey into the unknown that lasted five years.

You filmed in Egypt – as the story of the American/ Lebanese maverick is set there on the background of the 2011 uprisings. How does one has to imagine the artistic working process with such a political topic in Egypt at that time? Would it be possible under the current circumstances?

It wasn’t exactly possible when we started shooting in 2012. By 2014 it became an utterly insane endeavor due to the political situation in the country, which was steadily aggravating. Especially for foreigners carrying cameras. We could never afford a fixer or any form of security when we were there, our families were very worried and it became clear that we had to stop. After what proved to be our last trip, I remember us saying to each other “imagine Cairo was destroyed completely and we can never go back. What do we do with this material?”.

We were never interested in making a typical music documentary about Alan –he would never have agreed anyway and we are not exactly documentary makers. Neither did we plan to make a political film. Actually, at the time Greece offered us more political subject matter without spending a penny, if this had been our intention. It just happened that we were there with these people in historical times, and we experienced with them the aftermath of the so –called Arab Spring, what more and more looks like a political defeat. Our protagonists where active in the revolution, half of them were in a band that played in Tahrir during the 18 days, Eskenderella. At the point that we met them, all they wanted was to retreat to their privacy and play music, which comes naturally if you feel that you cannot effect change by being in the streets anymore. We were observing what was going on in the country, from inside their artistic bubble that was being permeated all the time.

They were trying to rehearse, to set up a concert, to function in general and they were witnessing endless stumbling blocks and obstacles.The film’s story unfolds around these obstacles and “interruptions” that made us all feel shut-down, repetitively. In the Arabic language there is a word for this particular feeling of depression. It’s called “h’bot”. One of the characters is trying to translate it in English in the film but proves untranslatable…

The band in the movie does translate old songs of Alan Bishop and the Sun City Girls into Arabic. How did people there and in general react to this hi coded artistic idea?

Translation is a central and recurring theme and a sort of a metaphysical backbone in this story, as we continuously experience the reincarnation or the re-appropriation of Alan’s poetry, songs he wrote many years ago, in the United States when he was at their age more or less in a different time zone and era. Knowing the lyrical content of his work, which is outré even by Western standards, when translated by Egyptians in their twenties, these songs gained a different momentum and came to express the experience of living at the time in Cairo. This almost felt like an alchemy, considering how old the songs were. Alan’s lyrics are strange, dark and ambiguous and this was a shock to the miniscule local scene, of course. Arabic poetry and songs, don’t traditionally deal with themes from Alan’s repertoire.

But that was the story four, five years ago. Right now the Cairo scene has opened up to various influences and experimentation. Musicians like Maurice Louca, Tamer Abu Ghazaleh, The Dwarfs of East Agouza, Islam Chipsy and Nadah El Shazly to name a few, are deservedly pursuing international careers nowadays, owing a lot to the tireless effort of record labels from the region like Nawa, 100 Copies and Nashazphone.

Could you name influences (film and directors) on the aesthetics of “The Invisible Hands“?

For practical reasons, since I was editing the film for three years -and had to cut it down from 400 hrs to 90 minutes – I unfortunately didn’t have the time, or the ears and eyeballs to watch the films of others for research or pleasure. But generally speaking, I cannot exactly trace my influences; I can’t relate to other films directly but probably to all the films that are embedded in my system. But I owe a lot to various stimuli and other forms of art and especially music, which as an art I am tending to respect more.

In this case, I guess inspiration came from the story of the band, the people that we met and the city in which it was unfolding, which became a sort of a character in the film. On an aesthetic level, Alan and the band’s music and the Sun City Girls’ legacy and artistic universe were of great influence. The film is in effect is a thickly layered, psychedelic collage of interrelated themes and stories that we are navigated through the story of the Invisible Hands.

There was also a very conscious decision that this film is going to be a narrative, although we both come from experimental areas of film and the visual arts. There was an urgency to speak loud and clear about what we experienced in Cairo (and Athens) and not experiment with form or do something obscure. Alan himself was doing his most accessible project in Cairo, why should we mess this up in our film?

I think though, that a narrative film with someone from the Sun City Girls in it, is an experiment by itself, if not an act of subversion.

What is it you are looking for in documentaries?

I like being offered questions that I take home when the film finishes. Usually I am offered answers, information I can find on the internet and dogma trying to be shoved down my throat. There are of course many refreshing and inspiring exceptions that make documentary one of the most exciting film practices nowadays.

Could you give us some insights in the filming process with Alan Bishop? Was this always a smooth process or did it also come to artistic discussion between you, was he for example also deeply involved in the process of selecting the material and the final cut?

When you deal with a real story and real people, you have to respect them and their views all the way through, because it’s their lives that you’re going to expose. Alan, Aya, Cherif and Adham trusted us and allowed us almost unlimited access to their lives. For this access, we were morally responsible not to misrepresent them.

This film was shot in Cairo but is built around intense and inspiring dialogue between Cairo, Athens and Seattle. All the characters were involved, but Alan was involved the most, as he was the catalyst that brought all of us together in what looks like a global network. I must have exchanged around 1.000 emails in five years with him, smoked thousands of cigarettes and usually some great music was playing in the background.

Alan is one of the most charismatic and inspiring people I’ve ever met. It would be a folly not to ask or get his advice when this was offered to me. We were all, including the band, very lucky to be around him. I can personally admit that his humor helped me deal with my depression and disillusionment and his defiance taught me to never give up. Which was much needed all the way in this film.

However, all the people involved helped it take the shape it has, and it shows, I think. Not only we became close friends, we all became part of the same project. “The Invisible Hands” is a band and a film and we already move like a combo now that the film starts circulating. Both Documenta and Berlinale present a film and a concert.

To come to the end of the interview. Could you name your highlight moment during filming?

I consider our time in Cairo maybe the best time of my life. Maybe Georges also feels the same. The film is filled with extraordinary and intense moments in this magical city. Do you believe in magic?

Yes, I do.

And lowlights?

Both directors and cast, we were all going through tough situations from a political, personal and economic standpoint. We reached so many times the abyss that I can hardly count. It’s all in the film if you look closely.

The film was first shown at Documenta 14 – how did that happen? How was your experience? Do you think it fit well in this context?

I was chosen to participate in Documenta with an earlier work of mine, “The Secret School”, a found kitsch educational film from the Greek Junta, which I somehow turned into an anti-nationalist “comedy”. Since every artist had to produce two works for two cities Athens and Kassel, I was asked come up with a new work. At the time, I was at rough cut stage of the Invisible Hands. They saw it and included it. To my surprise too, because it’s a narrative film. Sometimes people expect hardcore formalism from the films shown in an arts context and that’s probably why we get questions like this one.

If I can think about it from the outside, since some time has passed, I think it fit quite well in this particular and most musical of all Documentas. It was actually the first time ever that I saw an exhibition treating music and the musical process equally as all the other arts.

More info, tickets: https://www.berlinale.de/en/programm/berlinale_programm/datenblatt.php?film_id=201810879#tab=filmStills