The magic music of Umeko Ando

Sometimes music is a complete revelation. Take the case of Umeko Ando. Knowing nothing about her, suddenly the room was filled with this incredibly special, very atmospheric music.

You might describe Umeko Ando, who sadly passed away in 2004, as a Japanese folk singer – but once one starts to dig deeper the storyline is actually rather different.

Umeko Ando is a representative of the Ainu culture, who live on the most northern Japanese island of Hokkaido. The Ainu are an indigenous community only granted official recognition by the Japanese government as recently as 2008. Ando’s music is highly reflective of her Ainu background, the Ainu language and its instrumental traditions, including her playing of the mukkuri.

An album has just been released, a collaboration with Tonkori player Oki Kano on Pingipung.

Hello Oki, I heard Umeko Ando’s voice and her beautiful repetitive vocal style for the first time when I was in Japan last year. I loved it very much. It‘s surprising how few people in Europe know about her music. Your recordings with her have only been released on CD in Japan up until now. I want to thank you for licensing your recordings for this vinyl release.

Oki Kano: It’s my pleasure. Yes, this record Ihunke was her first CD, the recordings are from 2000, four years before Umeko Ando passed away. She was around 70 years old in these sessions and she was one of the few traditional Ainu musicians who was open to working with the younger generation and with new technology. I‘m a dub lover, therefore I like vinyl very much.

Who was Umeko Ando?

Umeko was born in Husiko Kotan, Obihiro in 1932. She always loved to sing and play the Mukkuri since she was very little. The Mukkuri is a local version of the Jew‘s harp made from bamboo and you can hear it all over the album. She became one of the most famous players of the Mukkuri, and she was also a member of Obihiro Ainu cultural preservation society. Umeko was one of the most important people in Hokkaido with traditional Ainu cultural knowledge.

How did you know her?

I met Umeko in the late 1990s, when traditional music still stayed in the community and the singing wasn’t passed on to later generations. Most young people lost the motivation to learn. I mean, people didn’t believe that they could sing any better than the old folks. So, singers in Hokkaido were getting old. Umeko was one of them, but she was someone special. Her voice is very much the authentic Ainu style, with a little bit of Minyo (Japanese folk) flavor in it. She studied Minyo when she was young, which is why Umeko could get used to a modern recording manner quickly. She loved new challenges. In Ainu culture there is a tradition of respecting the elder generation very much. Umeko was the first Ainu elder with the open mind to create new music with the new generation.

You say that Ainu culture had been oppressed, what is the story behind it?

It’s a very long story. The island of Hokkaido is located in the north of Japan, and the Japanese have tried to assimilate our culture over the centuries. The government forced the Ainu lifestyle to change because in their eyes the Ainu needed to be Japanese. If the Ainu were Japanese, then the government could prove that Hokkaido, Karahuto (Sakhalin), and the Chisima Islands were Japanese territory. When Umeko Ando was young, the Ainu language was forbidden. It was seriously tough to live with an Ainu identity back then. Her parents generation gave up speaking Ainu to their children to hide their identity in order to survive. But within the communities, Ainu language and music were still passed on to later generations. As Ainu people, we don’t have any desire to build a nation, but instead live in many regional communities.

What else do you mean by lost Ainu culture except language and music?

Everything is in danger including language and music. The Ainu could no longer follow their hunting traditions, we lost territory, and the trade became more dependent on Japan instead of our traditional economic relations with indigenous peoples of the Far East, with Russia and the Shin (清) Dynasty. Also it was forbidden to have tattoos. Under this strong discrimination, being Ainu was a shameful thing. Living as a typical Japanese person was the only way to survive.

You play a traditional Ainu musical instrument, what is this?

I play the Tonkori. It‘s a five-string harp which is held away from the body and plucked with both hands. It originally comes from the Ainu in Sakhalin which is the island north of Hokkaido. But I am not a Sakhalin Ainu, I belong to the Asahikawa Ainu.

What is the history of the Tonkori?

The Ainu don’t use written language, so nobody really knows where the Tonkori came from. One story goes like this: In 1860, around the time America tried to break Japan’s 300-year-old closed-country policy, the Japanese explorer Takeshiro Matsuura visited a small village called Otasan Kotan on the Okhotsk coast. There was an old man with white hair and a long beard. Looking into his eyes, Takeshiro knew he wasn’t an ordinary man. His name was Onowanku. He loved an instrument called Tonkori – he played this long, slim, five-stringed harp all day long, stopping only to eat and sleep. “Why do you play your Tonkori so much?” Takeshiro asked. “Japanese fishermen opened a new fishing ground recently. Ainu people have been working there very hard all day and night. There is no time for them to play the Tonkori, so in the end, nobody can make a good sound except me. My mission is to keep the Tonkori tradition alive – that’s why I play Tonkori all day”, Onowanku answered. One day Onowanku took Takeshiro to the beach. Onowanku sang a song on Tonkori with ten fingers under the hazy moon. Takeshiro was very impressed with his performance. After he left Otasam village, Takeshiro visited the second best Tonkori player on the island, but his playing was far from the quality of Onowanku’s.

World War 2 destroyed the Sakhalin Ainu culture completely. All of the Sakhalin Ainu were forcibly relocated to Hokkaido and lost their ancestral land forever. But it was not the end. Tonkori tradition had survived in Otasan Koran. New generations’ rhythms had been recorded in 1/4″ tapes after they moved to Hokkaido. These recordings are a milestone on the road to keeping Tonkori tradition on the right track and those tapes are our treasure.

Are you playing the Tonkori with a similar motivation as Onowanku, to keep the sound alive and beautiful in busy times?

Yes, but I also take it to new places and I design and build my own Tonkoris. My band is called Oki Dub Ainu Band, we use modern recording technology in the studio as a vital part of our music. I take the Tonkori around the world and play it in many countries.

Umeko Ando recorded traditional Ainu songs in your studio. How was that experience?

I decided to record Ihunke at my country house instead of the recording studio. The frogs in the first song of Ihunke were recorded at the pond in front of my house. I created new riddims for her songs, but some songs she improvised over an old Tonkori riddim, like “Battaki” and “Iyomante Upopo”. She always said Ainu music is all about improvisation.

Umeko is an Obihiro Ainu, and they didn’t have a Tonkori tradition. As I said, the Tonkori was born in Sakhalin Island, and the culture there is different. This album is the first attempt at “Obihiro meets Sakhalin” in Ainu history, and this is also the first album completely created and produced by Ainu. Umeko is like a blues singer who lived in the country. It was a lot of fun to record with her. Many Ainu hesitate to break from tradition – if Umeko hadn’t been so flexible, this album never would have happened. Sometimes our recording sessions were intense, we were proud and happy about making such beautiful music.

How intense?

Umeko loved beer. But she didn’t like how I pour beer. “I don’t like beer foam”, she said.

I’m curious about the meanings of the songs. They all sound very happy to my ears.

The title song “Ihunke” is a lullaby. There are many many versions of this song.

“Iyomante Upopo” is a song which is sung at the bear ceremony. Kamuy means God. The bear is one of the highest Gods. The Ainu word for bear is just Kamuy. The text goes like this:

“My family, little bear walk in the cage. Rubs his head, thrusts his head

Kamuy is standing up now

Rubs his head, thrusts his head”

What about “Saraba Iya Ko Ko”?

Saraba… it’s just a word. Nobody knows the meaning. Maybe it is a really old song. Some people say that Kamuy loves these old songs. This song sometimes also goes by the name “Ku Rimse”. It’s a song for a bow dance. A man finds a beautiful bird in the forest and tries to draw a bow.

A bow for killing the bird?

Yes, it’s about hunting, about killing the bird. In the end he gave up on doing it, because the bird was too beautiful. But maybe people added this other meaning later. That’s my guess.

Umeko Ando

Umeko Ando

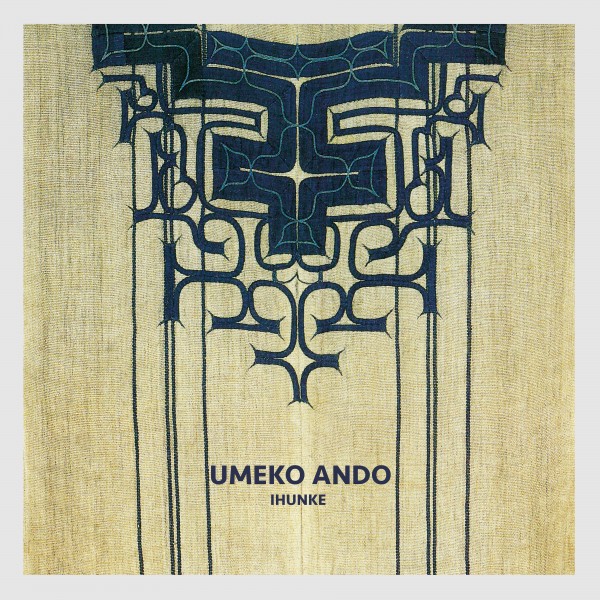

“Ihunke”

(Pingipung)

This Interview with Oki Kano was recorded and edited by Andi Otto in June 2018.

It was first published as the liner notes to the release, Kaput is happy to be able to republish it with kindly permission from the author and the label.